Josette Bushell-Mingo: The Revolution Will Be Staged

By Associate Professor Ryan Thomas Skinner, School of Music and the Department of African American and African Studies. This essay is about Josette Bushell-Mingo, who will be performing at Ohio State in October for Moving Subjects Week. The text is excerpted from Skinner's manuscript, Yellow, Blue, and Black: Social History and Public Culture in Afro-Sweden.

When speaking with Josette Bushell-Mingo, sparks fly. The actor, director, cultural advocate and social activist is a person whose charisma, intellect and passion refracts in all directions. Like lightning bolts, words and gestures chart circuitous paths through topics that are also emotions and relationships; topics that are also the subjects of art. As such, it can be hard to follow Bushell-Mingo’s train of thought, but it’s well worth the effort. In the presence of this British-born, Caribbean-rooted and Swedish-resident renaissance woman, the boundary between art and life disappears; at the same time, the African diaspora comes into sharp focus. On or off stage, she embodies and exudes her creative practice, which cannot be divorced from her concerns for and engagement with social justice, and the struggle to support and sustain black lives in particular. She embodies — through her art and life (as if these can be separated) — an expression of “Afro-Swedish renaissance” that insists on an emphatically and dramatically black presence in the Swedish public sphere, with no apologies. “It’s woke!” she tells me. “It’s renaissance that’s happening.”[1]

On April 18, 2016, Bushell-Mingo and I meet at hole-in-the-wall sushi shop in the trendy Hornstull neighborhood in Stockholm, where she lives. Accompanied by cups of miso soup and hot green tea, we are there to talk about her current theatrical project, En druva i solen, a Swedish adaption of Loraine Hansberry’s classic African American Broadway show, A Raisin in the Sun. Directed by Bushell-Mingo, the critically-acclaimed play has been on tour in Sweden for the past three months with the National Theater Company (Riksteatern), and it has just wrapped up a series of encore performances at Södra Teatern in Stockholm, one of which I was able to attend. Remarkably, Hansberry’s landmark play has never been staged in Sweden. Further, its predominantly black cast and crew represents another first for a culture sector that has long struggled to acknowledge and remediate an endemic lack of social and cultural diversity, on stage and behind the scenes. “Why the play has not been done before is the question,” Bushell-Mingo tells a reporter from The New York Times. “Every day we rehearse, it becomes more important.” David Lenneman, a Gambian-Swedish actor who plays the role of Walter Younger in the Swedish production, explains that the Swedish art world’s insensible “color-blindness” is part of a broader, societal problem. “You are told, ‘you are not black, you are Swedish, but when you try to be Swedish, you are not allowed in” (as cited in Kushkush 2016).

And yet, for Bushell-Mingo, En druva i solen is not primarily about the apparent failings of a normatively white Swedish culture sector. “This is not about the education of whites,” she explains, “this is about the education of blacks.”[2] As she sees it, En druva i solen, like A Raisin in the Sun before it, is first and foremost about the black experience and, more specifically, how a story rooted in African American history might translate and signify to a contemporary Afro-Swedish audience. “I’m interested to know what happens when the diaspora meets and they share their experiences,” she explains. “Not because I want to observe, but because I want to be part of it… I want to create a room where people can talk like this.” Bushell-Mingo’s intent is not to exclude white audiences, still by far the majority public for this and other national productions in Sweden, but she is interested in, as she puts it, “creating a room” for diasporic encounters. In her view, “the process of [staging] A Raisin in the Sun was historic not just because the play was being here for the first time, but [because] you were watching actors transform, claiming a space as black people.” Speaking of the cast members’ collective journey in staging En druva i solen, Bushell-Mingo describes the experience as transformational, revelatory and anxious. “You can see their soul shifting inside, some revelation, some understanding and also an element of fear.” This, too, is renaissance: to reimagine the present against the grain of an oppressive past can be both exhilarating and terrifying; to “claim a space as black people” in the wake of white supremacy is both bold and forbidding.

“I’m interested to know what happens when the diaspora meets and they share their experiences,” she explains. “Not because I want to observe, but because I want to be part of it… I want to create a room where people can talk like this.”

This has meant making space for dialogue and debate among black performers, audiences, and culture brokers, allowing them to constructively and critically explore their identities together around stories told from the Afro-diasporic archive. In this way, Bushell-Mingo invited members of the African-Swedish separatist group, Black Coffee, to attend a preview of En druva i solen and insisted that the post-show conversation privilege their voices. This caused some private consternation among white audience members in attendance, who cringed at this manifestation of apparent racial exclusivity in what they view to be a free and open, that is “liberal” (colorblind and anti-racist) society. In the face of such critiques, Bushell-Mingo is undeterred. “Our Afro-Swedish community does not have a home.” While Bushell-Mingo’s long-term vision is to create a permanent physical space for the Afro-diasporic arts in Sweden (about which more below), her initial efforts at diasporic “home-making” have focused more on repertoire, telling stories that foreground black lives, told from black perspectives. “En druva i solen is not going to change racism,” she says, “but it [does] give us a place to rest. It gives us a place to gain courage and it gives us the insight into argument, and what is possible if we lose” (see also Kronlund 2011). But Bushell-Mingo does not dwell on defeat. Daydreaming about future productions, she indulges in diasporic vision: “The first [work] will be an African play, which has Gods in it. I think it’s time the Gods came home, and that we see that. The second will be a re-imagining of a classic, like, let’s say, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, set in Carnival.”

Still, in diaspora, such dreams are often accompanied by waking nightmares. For Bushell-Mingo, the very real prospect of still more loss in the black community (of status, integrity, dignity and, indeed, life) demands a rigorous and often onerous curatorial method. She calls this, invoking one of her mother’s household refrains, “staying in the valley.”[3] Speaking of her Afro-diasporic audiences, she says: “I know you want to get to the top, but you need to stay in this bit… Stay in the darkness. Stay in the shit. Stay in the difficult stuff. Face it. Call it out.” In her view, it is no less important for her white audiences to “go down” and cohabit these spaces too, but their presence demands a particular ethics of listening, with a deference that goes against the grain of privilege. On the one hand, she stresses the learning that is possible from simply bearing witness and, on the other, the growth that is possible from simply being present. “You go through that experience together, and you walk out the theater together, and you say ‘I have seen, I have learned, I have witnessed. I understand something else about myself’” and, one might infer, about each other. In this sense, “Afro-Swedish renaissance” is also — and, arguably, always and already — about Swedish renaissance, about the “otherwise possibility” (Crawley 2017) that Sweden may be if space is made for its diasporic subjects to settle in, be present and “ta plats” (claim a place); of what could be if Sweden’s endemically intransigent public sphere catches up to the urgent pace of diasporic change.[4]

“You go through that experience together, and you walk out the theater together, and you say ‘I have seen, I have learned, I have witnessed. I understand something else about myself’”

But that’s easier said than done. “It is [Sweden’s] biggest Achilles heel,” Bushell-Mingo explains. “It will unhook this country.” There is a profound knowledge deficit about the African world, she argues, and that must be filled if Sweden is to acknowledge and accept a permanent black presence in its midst. “And then you’ve got a minority black [public], who are woke, we’re talking a sped-up version, we’re talking augmented woke.” This is, simply put, a diasporic community that is tired of waiting, and the societal tension, as impatience meets intransigence, is palpable. For Bushell-Mingo, this is where and why theater can make a difference. “We can’t stop the revolution when it comes, but we can slow it down.” Importantly, ‘slowing things down’ does not mean ‘bringing to a halt.’ Diasporic change, from Bushell-Mingo’s point of view, is as inevitable as it is necessary. “Slowing down” is, however, a conscious effort to critically reflect, creatively experiment and, perhaps, shift the stakes of social conflict before reaching a point of inflection. Theater “can give you breath,” Bushell-Mingo insists. “It can literally slow things down.”

This is the purpose, she tells, me of the National Black Theatre of Sweden, which officially launched in November 2018 and will begin staging shows in the autumn of 2019. By presenting a repertoire derived exclusively from the African world — including Afro-Sweden — the National Black Theatre seeks to fill the diasporic knowledge gap in Sweden. “It’s a theater company that produces some of the greatest and most important classics… from the African continent and [its] diaspora,” Bushell-Mingo explains. “That’s it. There isn’t anything else.” And by producing a public space where people from all walks of life can encounter each other through the performing arts, the National Black Theatre aims to “slow things down” — to promote a sustaining and salutary dialogue, on and off stage, across otherwise entrenched positions of difference. “What I’m interested in is this tension that’s happening… as woke is meeting resistance. This intersection,” she says. “The National Black Theatre can’t change things, but it can slow things down.” What happens next can’t be predicted. Art, like politics, as Stuart Hall once reminded us (1997), unfolds with no guarantees. But “when you program the fucking work,” Bushell-Mingo insists, “then the discussion happens,” and hopefully, “the art does what you hope it will, and that is to live and to grow.”

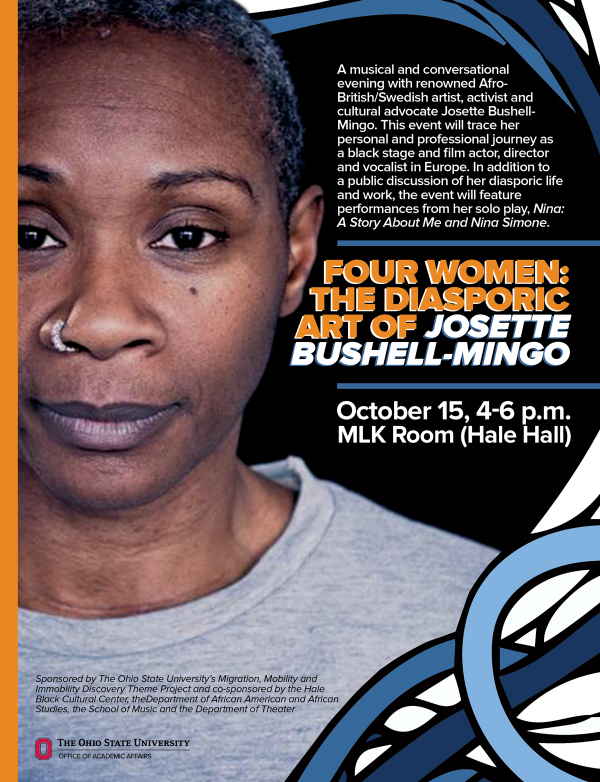

Artist, cultural advocate and social activist Josette Bushell-Mingo’s life and work embodies mobility and creation within the contemporary Afro-European diaspora. Bushell-Mingo is of Afro-Caribbean and British descent, though she has called Sweden home for the past fifteen years. As an artist, she is an actor, director and singer. In England, she has a well-established stage career, having worked major groups like The Royal Shakespeare Company. In 2006, she was named Officer of the Order of the British Empire. In Sweden, Bushell-Mingo is one of most sought-out public figures in the contemporary art world, as a musical and dramatic artist but also as a culture broker and public intellectual. In her role as advocate, Bushell-Mingo has worked tirelessly to bring marginal voices to the fore of Swedish public culture, particularly in theater. Some of those voices are ethnic and racial minorities. This past year, Bushell-Mingo founded the National Black Theatre of Sweden, the first of its kind. Bushell-Mingo’s cultural labor has also been distinguished by her creative work with the deaf community; she fluently signs in both Swedish and English. Bushell-Mingo is currently head of Acting at Stockholm’s University of the Arts. Once again, this is a historic first. She is the first woman and person of African descent to hold the position.

Works Cited

Crawley, Ashon T. 2017. Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility. New York: Fordham University Press.

Hall, Stuart. 1997a. “Race: The Floating Signifier” (public lecture). Northhampton, MA: Media Education Foundation.

Kronlund, Andrea Davis. 2017. “Josette Bushell-Mingo: a story about blackness and kick-ass theatre.” Krull Magazine.16 March

Kushkush, Isma’il. 2016. “‘A Raisin in the Sun’ Through the Eyes of Afro-Swedes.” New York Times. 2 February. nytimes.com (last accessed on 5 July 2019)

[1] Interview with the author, 22 June 2017 (Stockholm, Sweden).

[2] Interview with the author, 18 April 2016 (Stockholm, Sweden).

[3] Interview with the author, 22 June 2017 (Stockholm, Sweden).

[4] Ashon Crawley, in his seminal Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (2017), defines “otherwise” as “the subjectivity in the commons, an a subjectivity that is not about the enclosed self but the open, vulnerable, available, enfleshed organism.” For Crawley, “otherwise possibility” is a theoretical and methodological means “for thinking blackness and flesh, for thinking blackness and performance, as gathering and extending that which otherwise is discarded and discardable, those two modalities as modes of being and existence” (24-25).