About the Author

JACK FEDERINKO (HE/HIM)

Jack Federinko is an undergraduate fellow in the Global Arts and Humanities’ 2023-2024 Society of Fellows cohort. Federinko is pursuing a BFA in dance with focuses on dance theory, history and notation. His research explores the historical implications of dance notation, focusing on the absence of archival materials for African Diasporic aesthetics of dance. He aims to augment the voices of West African, Tap and Afro-Contemporary artists overshadowed by historically racist and white supremacist frameworks.

Project Overview

This project explores the adaptation of dance notation to accurately represent African Diasporic aesthetics of dance — addressing the historical exclusion of Black artists from proper preservation and documentation. Focusing on West African dance notation with secondary research on Tap and Afro-Contemporary styles, this research aims to showcase the evolution of dance notation towards a more inclusive and equitable practice, fostering a dance language that aligns with the concept of "Freedom Dreaming."

Introduction

This project delves into the intricate realm of dance notation, exploring how notators have innovatively crafted systems to capture the nuances of African Diasporic aesthetics of dance, mainly by focusing on the "aesthetic of the cool". Traditional dance notation systems — particularly Labanotation, created by Rudolf Laban in 1928 — have excluded Black artists, resulting in the loss of entire decades of Black dance.

The effort to document the cultural and individual expressions of West African rhythms is underscored by the creation of the "Dynamic Phrase," a notation strategy developed by dance notators Odette Blum, Vera Maletic and Lucy Venable and a more current system created by ethnomusicologist and Africanist Doris Green’s percussion notation system: Greenotation.

In the domain of Tap, Joan Hill's visually-oriented system offers valuable insights into representing the rhythm inherent in this distinctive style. Employing a rhythm-focused notation approach, Hill utilized a traditional music staff and collaborated with tap dancer Leon Collins to correlate individual tap steps with musical notes.

The reconstruction and recovery of Afro-Contemporary dance is an ongoing process as many works created by Black artists are slowly being pieced back together. Current works of Afro-Contemporary dance are being more frequently preserved thanks to the help of innovative approaches to notation. By delving into the work of four-time Bessie Award-winning choreographer and Professor Emerita of Dance at Ohio State, Bebe Miller, and her influential work, Prey, and the notation by Ohio State Professor of Dance, Valarie Williams, I will explore the various strategies employed to document the aesthetic of the cool in contemporary dance.

“…The principle of coolness or, as Thompson termed it, ‘an aesthetic of the cool.’ The Europeanist attitude suggests centeredness, control, linearity, directness. Energy is controlled by form. The Africanist mode suggests asymmetricality (that plays with falling off center), looseness (implying flexibility, vitality, and the possibility of improvisation, even danger), and indirectness of approach. Here energy dictates and controls the form.”

BRENDA DIXON GOTTSCHILD

Analyses

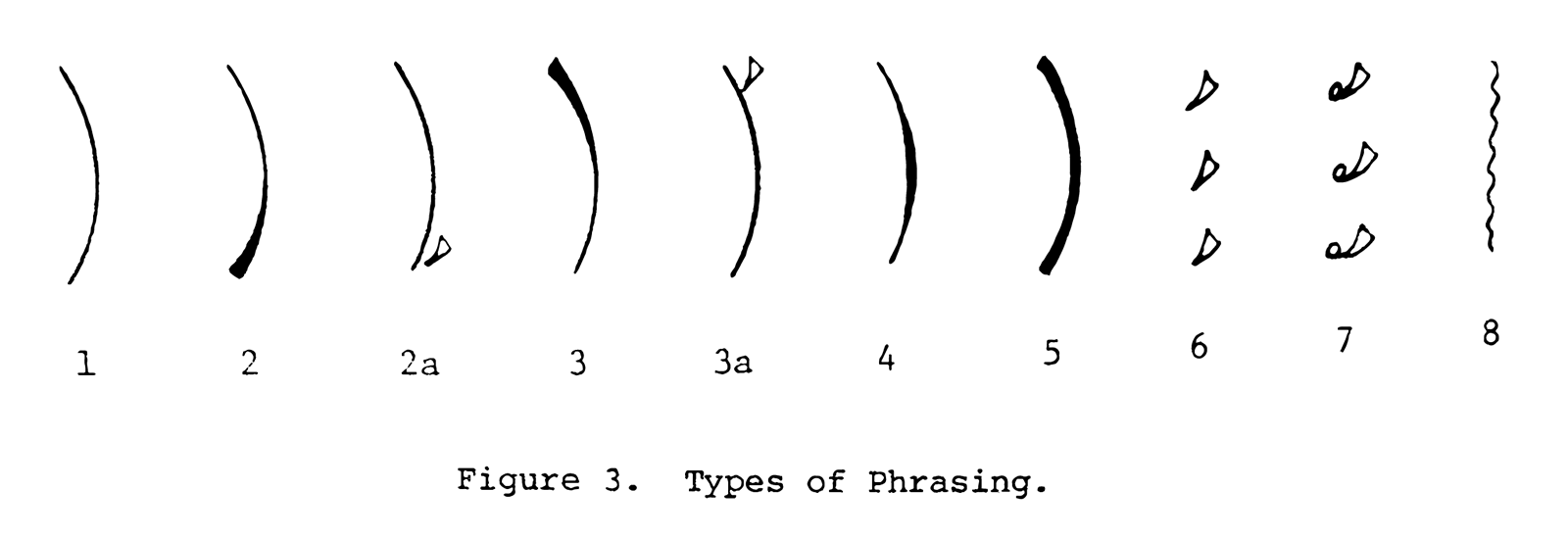

In Blum's scores of Ghanaian social dances, Melatic introduced three innovative symbols: ”accented," "resilient" and "vibrato," designed to articulate nuances in movement phrases. These symbols, represented by a large parenthetical, serve as a valuable tool for notating the distinct qualities of various movements. While effectively capturing the intricacies of multiple movements, they fall short in portraying the rapid switches in the textures and dynamics of West African dance.

In contrast, the drum score created by Green, encompasses diverse patterns of words, maintaining its primary purpose of recording the specific hand(s) engaged in slapping the drums, without incorporating Melatic's new dynamic phrasing symbols. To keep the dancers on time, the drum score utilizes a pattern of words: “GO, Dzi, Dzit” that signify the right hand, left hand, and both hands striking the drum respectively. Including a meticulous floor plan in the notation is a highlight, offering a detailed visualization of the exchange and interaction between dancers, particularly during traveling steps — a crucial element in West African rhythms (varieties of West African dance are referred to as rhythms rather than styles). Furthermore, Greenotation captures the aesthetic of the cool by meticulously documenting individual variations and expressions of each dancer, showcasing the rich diversity inherent in West African dance.

The Joan Hill System of Tap Notation includes a vernacular score that articulates the names of tap steps, aligning seamlessly with the timing of the musical staff. As it progresses, the system evolves into a more intricate form, featuring complex tap steps, each possessing its unique musical note structure; for instance, a riff may consist of two eight notes stacked atop each other directly linked to two stacked half notes. To clarify, a riff is when the free foot performs a toe dig, a scuff, and then the standing leg performs a heel drop- a performance of three distinct sounds in quick succession that can be further manipulated to include additional steps/sounds.

This approach stands as a superior representation of tap rhythm, emphasizing its similarity to West African dance, where rhythm plays a paramount role in defining the style. In contrast to Labanotation, which effectively captures the spatial aspects and placement of movement, it falls short in portraying a concise rhythm structure, lacking detailed counting or a rhythm staff.

The notation score for "Prey" by Valarie Williams and Bebe Miller exemplifies the intricate challenge of precisely capturing complex movements through symbolic representation, necessitating descriptive text. It notably highlights the profound connection to gravity, akin to the characteristic essence of West African dance. Within this score, the notation portrays a polyrhythmic movement structure, a critical component of African Diasporic forms of dance, capturing the rapid footwork alongside the deliberate, slower motions of the arms and torso.

Incorporating descriptive text, such as in measures five and six of the "Birds" section, enhances the accuracy of embodiment. For instance, the side note accompanying these measures guides the performer with the instruction, "Physical Intent: This is a struggle, slow as you can," ensuring a nuanced and spiritually-resonant execution.

In essence, the exploration of notation within African Diasporic aesthetics becomes a form of freedom dreaming in itself — a continuous process of pushing artistic boundaries, imagining new possibilities, and striving to encapsulate this "aesthetic of the cool". It reflects a commitment to preserving and evolving the cultural heritage embedded in these forms of dance, contributing to a vision of artistic freedom that transcends conventional limitations.

- West African:

- Blum's utilization of innovative symbols in Ghanaian social dance scores demonstrates an attempt to articulate nuances in movement. Yet, it fails to capture the rapid switches in textures and dynamics characteristic of West African dance.

- Green's drum score, though not incorporating Melatic's dynamic phrasing symbols, adeptly maintains its purpose in recording specific hand movements, emphasizing the crucial element of traveling steps in West African rhythms.

- Tap:

- The Joan Hill System of Tap Notation, evolving into a more intricate form, stands out as a superior representation of tap rhythm, underscoring its resonance with West African dance styles.

- In contrast to Labanotation's spatial emphasis, it lacks a concise rhythm structure.

- Afro-Contemporary:

- Williams’ Prey notation grapples with the complexity of capturing movements symbolically, incorporating descriptive text to enhance the spiritual accuracy of embodiment. Collectively, these notational strategies reflect the ongoing exploration of capturing African Diasporic aesthetics, showcasing the rich diversity inherent in these dynamic dance forms while pursuing the elusive "aesthetic of the cool."

- Armstrong, Joan Hill. “The Great American Art of Jazz Tap: Joan Hill System of Tap Notation.” vols. 1-6, 1983, Joan Armstrong Hill, all rights reserved.

- Bales, Melanie & Karen Eliot. “Dance on Its Own Terms: Histories and Methodologies.” May 2013, pp. 1-19. Oxford Scholarship Online, doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199939985.001.0001

- Blum, Odette. Investigation Into Ghanaian Dance, 1982. Notations by Odette Blum, 1982.

- Coles, Charles Honi. “Coles’ Stroll,” 1986. Notation by Sheila Marion, 1995, Department of Dance The Ohio State University.

- “From Hand Clapping to Water Drums: Music of Africa's Percussion Instruments.” YouTube, uploaded by Patricia Nelson, 12 March 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eBPiNM7Ns94

- Gottschild, Brenda Dixon. “The Diaspora DanceBoom (Dance in the World and the Diaspora DanceBoom, brendadixongottschild.files.wordpress.com/2010/07/diasporadanceboom9_04.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar. 2024.

- Green, Doris. “Greenotation: From Pitman Stenography to Greenotation/Labanotation.” International Council of Kinetography Laban, 2013, pp. 209-223.

- Green, Doris. “Makwaya,” 1969. Notation by Doris Green, 1984-1985.

- Green, Doris. “Sabar,” 1989. Notation by Doris Green, 1989.

- Jones, Bill T. “Fever Swamp,” 1983. Notation by Virginia Doris, 1988.

- Miller, Bebe. “Prey,” 2001. Notation by Dr. Valarie Williams, 2001.