Dancing with Devils Interview with Pamela Espinosa de los Monteros and Leonardo Carrizo

Dancing with Devils Interview with Pamela Espinosa de los Monteros and Leonardo Carrizo

The Dancing with Devils: Latin American Mask Traditions online exhibit is now available for viewing here! The exhibit will also have a virtual tour scheduled for March 22nd, 2021 at 11:10AM EST on Zoom (register here). The exhibit is supported by the K’acha Willaykuna Andean and Amazonian Indigenous Arts and Humanities Collaboration through an Ohio State Global Arts and Humanities Discovery Theme grant. Included is a conversation with exhibit curators Pamela Espinosa de los Monteros, the Latin American, Iberian and Latino/a Studies Librarian with Ohio State University Libraries, and exhibit photographer Leonardo Carrizo, a multi-platform lecturer for the School of Communications. Together we discuss the newly acquired Latin American mask collection connected to the exhibit, the challenges posed by the pandemic, and the importance of narrative construction connected to indigenous culture.

Special thanks to fellow curator Michelle Wibbelsman, Associate Professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese; Ohio State alumnus and retired Professor of Art at Barton College, Mark Gordon, for donating his mask collection to the Center for Latin American Studies at Ohio State; CLAS Assistant Director, Megan Hasting, who helped coordinate shipping and receipt of the donation as well as a CLAS Virtual Coffee conversation with Mark Gordon; and Ken Aschliman, Exhibits Coordinator at The Ohio State University Libraries, who helped design the digital site. Other supporters and collaborators include The Ohio State University’s Center for Latin American Studies, the K’acha Willaykuna Legacy Preservation and Knowledge Equity Working Group, and librarians Melina Frank and Molly McGirr from the Lakewood Public Library in Cleveland, Ohio.

Andrew Mitchel (Graduate Research Associate for K’acha Willaykuna): So just to start us off, where did the mask collection come from?

Pamela: The Center for Latin American Studies was approached by Mark Gordon, Professor of Art at Barton College and an Ohio State alumnus, who was interested in donating a collection of Latin American masks gathered during his dissertation studies. Mark had visited different mask-makers throughout Latin American to learn about their artistic craft and learn about the materials used to make masks. He would go on to draw inspiration from their techniques for his own artwork and instruction as an artist. As Mark was preparing for retirement, he was looking to donate his collection. When the mask collection was accepted by CLAS, the Center asked Mark if he would be willing to give a small lecture about them. The lecture was given in the summer of 2020 (you can view it here) and helped to contextualize the masks in this exhibit. In parallel, Professor Michelle Wibbelsman was able to connect the exhibit project with Leonardo Carrizo and I’ll let Leonardo take the story from here.

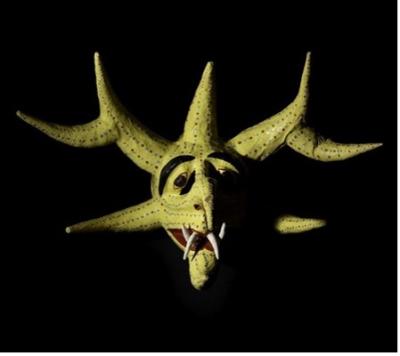

Leonardo: Professor Wibbelsman and I had collaborated before, since she does a lot of research in Ecuador and with Andean culture. I also worked in Ecuador, mainly in documentary work including photographing the region’s culture and people including documenting many festivals. One of these festivals, a very important one, is the Diablada de Píllaro. At this festival, not only do you have the devil characters as performers, but you also have several other characters. It’s a big cultural event that lasts six days in January from the 1st to the 6th. I was lucky enough to be there to document it, including following a particular group from beginning to end and learning from a mask-maker. So, it worked out extremely well that we had the mask collection from Professor Mark Gordon and that my photos could accompany these items. For the exhibit, we had both the tangible masks and the photographs we could use to describe the festival in Ecuador. We had a lot of great content to make this exhibit happen.

Andrew: So, I wanted to ask about creating an online exhibit. How has that worked, and what has displaying the masks in this manner done that is different from an in-person exhibit?

Pamela: So, let me start by saying that this was supposed to be an in-person exhibit. We were so excited to show off the real artifacts and bring people up close to the masks. The team coordinated getting the masks to campus and received the support of student curators for The Andean and Amazonian Indigenous Arts and Cultural Artifacts Collection to clean, measure and prepare them for display. Together we engaged in many discussions about which masks to feature. The goal was to display Leonardo’s beautiful photographs alongside the artifacts to create an immersive experience. Visitors would be invited to look at the physical masks and the mask in context which were photographed inside the festival. At the time, we had received permission to display the photographs in Thompson Library alongside the exhibit cases. We also formed a partnership with the Lakewood Public Library in Cleveland to curate a sister exhibit there. Then, a week before we were to install the exhibit, the pandemic hit. As the library transitioned to virtual services, we were approached to make this a virtual exhibit. Prior to all this, Leonardo was gracious enough to lend his talent and expertise to photograph all the masks as a way of featuring photographs of masks that we were not able to fit in our exhibit display cases. I’ll let Leonardo talk a little bit about his process in doing that.

Leonardo: So, we had created a time-lapse video in order to tie the donated masks to the photographs from the festival as they represent two cultural traditions from different regions. I created a photograph of each mask set to display in Thompson Library that could be shown at the sister exhibit in the Lakewood Public Library in Cleveland. It was a great opportunity to photograph the masks as they were cleaned, measured and made ready for display. I actually went to one of the study rooms at the library to take the photos. I was there with my professional lighting equipment and took several hours to create the photographs. They’re beautiful masks, just visually stunning! As Pamela said, with the pandemic we could not do the in-person exhibit and so the library came with the idea for the online exhibit which gave us another avenue to explore. I mean we were ready to go, we had even printed the poster-sized images for the exhibit, they’re very big. Another thing, we as curators had already designed the in-person exhibit with a space in mind. The space had informed our exhibit’s design and narratives. We had selected different sized images because they were going to fit in a particular physical space in Cleveland. Again, that’s something you have to be able to do when you’re working on any type of exhibit. We had already done a lot of that design legwork, so when we decided to do it online, we figured out we could follow the same flow and provide a similar layout and experience. Pamela and I had already drafted the exhibit labels and we intended to follow the in-person exhibit closely. We received lots of help from Ken Aschliman, Exhibits Coordinator for University Libraries. Ken guided us through the conversation process. The page layouts and the text on the online exhibit attempts to mimic what somebody would experience in the in-person exhibit.

Andrew: Why is it important that we preserve these items? How do you hope people will learn from this exhibit?

Leonardo: This ties in with my own work and my collaborative work with Professor Wibbelsman. You do not ever want to take pictures just to put them on your desktop. You need to share the work, you need to publish it, people need to see it, and learn from it. That’s the driving force of all of us who worked on this project. We have this shared attitude: having the artifacts is great, having the images is great, but you need to show them. They don’t benefit anybody if they’re in an archive or room or hidden away displayed on my wall somewhere. That’s not enough, you need to share it with the public, with other academics, and other people so they become and remain a living object, so they have a life of their own instead. This is also how I approach my photography. I don’t ever want what I do to be static. Though they’re photographs, I want them to be out and about, and Michelle has that same type of approach and vision, as does Pamela, who I’m sure is going to tell you this same thing and more. But that’s my approach as a photographer, this work needs to be shown and have a life of its own.

Pamela: The whole purpose of being a Lain American Studies librarian is connecting people with the region. Some people have the privilege of being from there, traveling there; and a lot of other people may not. So, this exhibit is an opportunity to engage with another culture and to see how rich and profound these rituals and festivals are. These festivals have a rich cultural fusion we can all learn from. The knowledge equity piece associated with this exhibit is also a vital part of the work for me. What narratives and cultural representations are we presenting on our campus? A lot of people are familiar with Carnival, but they may not be familiar with diabladas, and we’re so lucky to have someone like Leonardo at OSU who has been able to build connections with Andean communities, who has put himself in those spaces, who has been able to capture something very authentic and to do so with ethical considerations and grace. The exhibit can now take his work and display it and put people in touch with the festival. I’m grateful to be able to work with Leonardo and Michelle on these types of projects. Not having this be in-person was a little heart-breaking, because engaging directly with masks as primary materials in-person provides another level of experience. But we hope that the online exhibit, especially the way we’ve designed the Diablada (Devil Dance) exhibit section may invite participants to see a whole progression of the dance. It’s inviting people in to see this in a new way. This is getting to the heart of our K’acha Willaykuna Collaborative of really making space for indigenous art and artisans from the Andean and Amazonian region. As a result, we have spent a lot of time thinking about how other people will engage with the exhibit. There’s been a lot of conversation between Leonardo and I about how to place the photos, which is a different approach to scholarship and information. The process has been really creative. We hope that people who visit the exhibit will be able to take something away from it. It’s different from reading an article or a book about this subject, and hopefully it complements a more traditional method of learning. Plus, Leonardo’s ability to capture these images and the thought that goes behind every image is something that merits more unpacking.

Leonardo: The only thing I will add to that is something we’ve discussed previously in terms of how you get these images. There are thousands of people who go to the Diablada festival and as a result there are thousands of images of it. The difference with the images included in this exhibit is the approach I’ve taken as a documentary photographer to get a little closer and more intimate to the experience. So, what you see in the exhibit is the result of following just one group from the start to the end of their festival route. I immersed myself in the festival with them. That’s what the audience is going to be able to see in the exhibit—the behind-the-scenes, what everybody does before the parade in the main square. The photographs follow one community journey from the start to joining the main festivities where thousands of people gather. The photographs show the documentary style. I’m not just photographing the festival. Here we have main characters, the characters of the community, this is their diablada, this is where they meet, this is where they practice, this is how they walk down into the square. I walked with their community. They come down the mountain and make stops and pick up more people and then they proceed into the main square. So that’s one of the main things we worked on with the exhibit, just to show what the other people don’t see. So again, you can go take these photos, but they don’t become personal; they’re would just be beautiful cool images. But if you’re doing this deeper work you have to be part of it, so you have to gain trust, and to get that you need to invest time, that’s all that goes in to better representing the community. Especially since this is their event, it’s not our event, when you photograph from the outside, you’re just photographing the show, but it’s not just a show. So, I wanted to get closer and go behind the scenes. And there is an approach or a method to doing photography in this way. You have to be more aware and look for it. Otherwise, it’s not going to happen. You have to think about trying to tell this bigger story, and if not, you’re just going to have a collection of lots of pretty pictures but lacking the depth of what’s actually behind the festival.

Pamela: It’s true, and Mark Gordon had the same kind of take on this. He really went out of his way to find the mask-makers to create this collection. He respected them at a time when there was very little scholarship about mask-making traditions in Latin America. He really viewed it as an art form. He took inspiration from their work throughout his career. So, Mark and Leonardo have created a model for how to approach this type of artifacts and traditions, not to mention how to engage with the community which is relevant to counteract an extraction model and instead promote a more collaborative approach. So, there’s something that each one of us is taking away from this exhibit. I’m very excited that we have faculty that study these festivals and bring this expertise to OSU. This is a true area of study that can really tell you a lot about a place, its culture and its historical importance. So, I hope this exhibit can reshape students’ approach to Latin America culture and research.

Leonardo: Just another thing, as a project collaborator you have to be able to speak the same language and think about this the same way to make something like this exhibit happens, to have so many people collaborating, you want to get it right, be respectful and aware. You want the public to ask questions, but you have to do it in a manner which makes sense. A lot goes into an exhibit behind the scenes, with the curating, editing and many, many meetings. You need the right team to do it right; everybody has to agree and be on the same wavelength. That’s what I enjoy since that did happen and continues to happen. We’re still planning other things to ensure this work gets seen so others can learn from it and use it. To have that mindset, you need to have a good team of people invested in the project and promoting and working together. That’s where Pamela’s work is so valuable. Speaking to someone like her who speaks the same language in terms of thinking about these visuals and the underlying narrative is special. It can be hard across disciplines to understand each other. I’m a visual person and talk with visual narrative. If somebody doesn’t get that we might not be able to work together, or be in conversation, but Michelle, Pamela, Mark and I are in concert and work together well towards the same goal.

Pamela: It’s definitely been a team effort. For me this experience has changed how I look at masks. I no longer see them as static artifacts, now I see the community behind them, the purpose and intentionality behind the materials used to create them, many times sourced from the local environment, and how this unique artform informs the dancers ultimately wearing the masks. So, what happens as you work on this is, you start with a mask, but the connection is actually to the human being who puts on the mask and the community who uses the mask for their traditions. So, it really has changed how I look at these items. Our team associated with the Andean and Amazonian Artifacts collection look at these items as part of a living culture, so the exhibit goes well with the rest of the collection. And Leonardo has seen this festival in-person, so the process of putting it up is honoring what he saw there and this authentic experience he had, which is something those of us without the privilege of seeing and experiencing it in that way cannot bring. Having a team helps us keep the connection to the festival. We’ve tried as much as we can to honor this connection as we work on the exhibit. We are also grateful to University Libraries’ exhibits team especially Ken Aschliman who helped to create this exhibit.

Leonardo: And we do hope this can be in-person soon. That is still the final goal here. And one of the things we want is for there to be a traveling exhibit to other locations. That’s why we were working in Columbus at Ohio State and in Cleveland, the public library there as well. We wanted to bring this around Ohio to show people about la Diablada de Píllaro and the other masks, to show it in public spaces around the state. That was the initial goal we still hope to do once people are free to move about again once the pandemic is over.

Pamela: We think it’s important to note, too, that these festivals did not happen this year, and what a loss that has been. The devastation that this pandemic has had on indigenous communities around the world is something that we all need to be aware of and keep in mind. We are all struggling of course, being in isolation, but it has really hit some communities more than others. So, we wanted to be cognizant of that fact. Hopefully in time we can gather again.

Andrew: Thank you both so much for your time. And for our readers, please be sure to join us on March 22, 2021 at 11:10AM EST on Zoom (register here) for the virtual tour of Dancing With Devils: Latin American Mask Traditions!