Why Cross-Disciplinary Research Matters | Interview with Jacob Risinger

The following interview of Jacob Risinger was conducted by GAHDT Graduate Administrative Assistant, Eileen Horansky (PhD student, English).

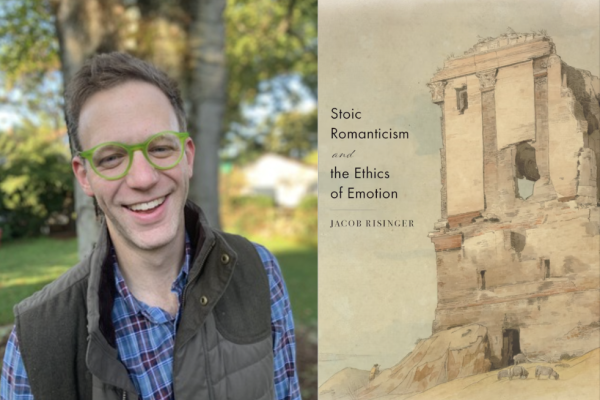

Jake Risinger writes and teaches about transatlantic Romanticism and the literature and philosophy of the long eighteenth century.

His book, Stoic Romanticism and the Ethics of Emotion, was published by Princeton University Press in 2021. Taking up a range of writers from Wollstonecraft and Wordsworth to Byron, Mary Shelley and Emerson, Stoic Romanticism illustrates how the austerity of an ancient philosophy, a central preoccupation in a world destabilized by the French Revolution, was not inimical to Romantic creativity, but vital to its realization. He is currently at work on a book about the unruly development of “power” as an aesthetic concept throughout the Industrial Revolution.

Eileen Horansky: Can you tell us about your current research project on “power” in Romantic writing and the Industrial Revolution? To what degree are cross-disciplinary perspectives or methods important to this project?

Jacob Risinger: In almost all the stories people tell about Romanticism, it’s portrayed as a movement in art and literature that emerged in reaction to the Industrial Revolution, or even in opposition to it. Think of Thoreau moving to Walden Pond, or Wordsworth writing grumpy sonnets about the railway’s arrival in the Lake District. I’ve been reexamining this conventional wisdom, and exploring the sustained interest that many Romantic writers took in new breakthroughs that allowed for the generation of industrial power. Take Percy Shelley, for example: he was an infamously ethereal poet, and a vocal critic of working conditions in factories. But he was also a financial backer of steam power, someone who thought that steam was a radical, even imaginative force that—properly channeled—could change the world for the better. Thinking about examples like this, I’ve come to see Romanticism as a moment oddly like ours: a point in which technological optimism and skepticism overlapped in productive ways.

One of the pleasures of this project has been a renewed sense of how cross-disciplinary thinking is more than a present preoccupation. I’ve certainly learned a lot about Shelley’s steam fixation from talking to colleagues studying the history of science and engineering, and I’ve been brushing up on the economics of energy production in the eighteenth-century. When I was a GAHDT faculty fellow last year, colleagues with a background in art history helped me think more capaciously about J.M.W. Turner’s depiction of industrial technology. Conversations like these have been a good reminder that in the Romantic period, cross-disciplinary thinking wasn’t the exception but the rule. The writers I’m studying weren’t cloistered in English Departments—they were out about in the world, and had formative friends who were doctors, scientists, industrialists, politicians, and engineers. It’s been fun to try and recapture their collaborative energy.

EH: What do you see as the major challenges of conducting cross-disciplinary research? What do you find most rewarding?

JR: The best thing about working between the disciplines is the experience of stumbling onto new terrain after years of focus. In my home field of literary studies, I’ve slowly acquired a sense of the lay of the land: I know what questions my colleagues are asking, and I understand how the field has been shaped over time. I have a pretty clear sense of what counts as a new contribution to knowledge, and when I’m up against a new question, I know where to look for answers, and how. But all bets are off when leaving that familiar territory behind. In stepping into new disciplinary terrain, there’s a thrilling sense of disorientation. How do I know who to read, what’s new and compelling, what’s out of date? Sometimes I get to learn from scratch—an experience at once exhilarating and humbling. Each book you read seems to generate its own massive reading list.

But if crossing into a new discipline is a challenge, it also facilitates one of the rewards: the conversations and collaborative exchanges that make doing interdisciplinary work possible. No field of knowledge need be entirely disorienting if you have someone to help you navigate it.

EH: What ethical considerations drive your interests in Romanticism and the literature of the 18th and 19th century?

JR: I’ll borrow a line from Percy Shelley, who claimed that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”—and I’d put all due emphasis on unacknowledged. For me, it’s been exciting to think with students about how writers in this period helped forge new ideas about nature, the imagination, and human emotion that still inform some of our attitudes in the twenty-first century.

Romanticism and the Anthropocene are chronologically linked, and writers from this period inaugurated a tradition of using literature to think about how to live ethically and sustainably in a threatened world. Anyone who’s ever approached the imagination as an asset rather than a liability owes a debt to the Romantics. Finally, this literary moment I keep coming back to is one that starts to explore the ethical possibilities of human emotion, as well as some its pitfalls. It might sound trite, but I really do think that revisiting this literature isn’t just a rearguard affair: thinking through what the philosopher Charles Taylor calls “sources of the self” might also prime us to ask new questions.