Why Cross-Disciplinary Research Matters | Interview with Lyn Tjon Soei Len

The following interview of Lyn Tjon Soei Len was conducted by GAHDT Graduate Administrative Assistant, Eileen Horansky (PhD student, English).

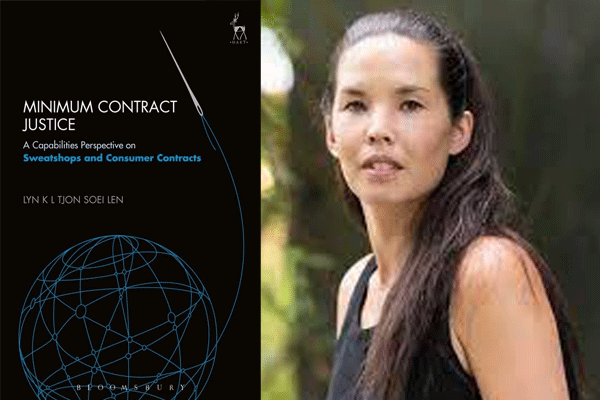

Lyn Tjon Soei Len is an assistant professor in the Department of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies and a GAHDT Faculty hire whose work focuses on the relationship between private law and social injustice. She is the chair of the board of Bureau Clara Wichmann, a feminist strategic litigation organization in the Netherlands. Her book, Minimum Contract Justice, explores the intersection of social injustice and contract law through the case of consumer contracts for goods produced by women in global sweatshops.

Eileen Horansky: Can you tell us about your current research on feminist legal methods and social justice in private law? To what degree are cross-disciplinary perspectives or methods important to this work?

Lyn Tjon Soei Len: I come to my work with a feminist awareness of the law’s complicity in social injustice and a desire for social change. Feminist movements often engage public law, which governs vertical relations between the state and persons. I focus on private law, which regulates horizontal relations between persons. As a site where power and distribution of (dis)advantage is organized, private law is often overlooked. Exposing private law’s complicity in social injustice is a key aim in my work because of its foundational role in coding social injustice through selective legal privileging. Accordingly, my work can make contributions in, and across, feminist studies and legal studies.

In previous work I have addressed various dimensions of injustice in the contractual coding of consumer vulnerability. More recently, I have integrated more closely my feminist legal scholarship and transnational feminist legal activism through a collaborative project on the private harms of sexist and racist hate speech, which emerged in the course of my work for a feminist strategic litigation organization in the Netherlands. This project is grounded in feminist and critical race theory, which center lived experiences of oppression as a source of legal knowledge.

EH: What do you see as the major challenges of conducting cross-disciplinary research? What do you find most rewarding?

LTSL: One major challenge to cross-disciplinary research is evaluation. Work that goes outside of the established pathways of knowledge production tends to be approached with suspicion regarding its validity and credibility in academia. Established criteria for evaluation may fail to appropriately value important contributions or attribute disproportionate weight to certain forms of research labor. Evaluation problems can also impede our understanding of certain patterns of injustice. For instance, when feminist methods are viewed as suspicious within private legal knowledge processes, feminist insights into the relationship between private law and social injustice remain marginalized. The stakes of such marginalization are high.

Time can be another important challenge, particularly when cross-disciplinary research involves collaboration with others across disciplines or outside of academia. There is a large time investment needed to establish research processes with others, communicate and work through taken for granted assumption and ethical commitments, and understand each other’s approaches and contributions. Though time consuming, the collaborative aspect of research can also be incredibly rewarding.

EH: What ethical considerations drive your interests in the issues of law, social justice and gender?

LTSL: As a feminist scholar, I’m committed to a critical stance towards the role of law in social injustice. I believe it is important for struggles for social justice to engage critically the way in which private law functions to justify and legitimate unjust arrangements. For instance, private law’s coding of certain relationships as economic and certain assets as wealth-creating helps to maintain social hierarchies across gender, race and other vectors of social division. My ethical commitment to struggle towards social justice is expressed in my work to expose such private law complicities because I see this as an important aspect of the possibility for social change.

In my engagement with strategic feminist litigation, I’m always aware that law is also an important site for marginalized people to seek recognition and harm reduction even when law and legal institutions function as tools of power and oppression. Feminist scholarship and strategic litigation have been the important investments through which I engage gender oppression, but they are ethically-complex investments for me. For instance, in feminist strategic litigation, the overarching interest is to change oppressive law and legal structures, but that interest does not always align with the interests of marginalized individuals in a particular legal case. Critical feminist legal arguments that can serve social change often decrease chances of winning a case or provoke backlash. I find that moving forward through these complexities is only possible in collectivity with other feminists.

Other interviews in this series:

- Amy Youngs (Art)

- Christa Teston (English)

- Michelle Wibbelsman (Spanish and Portuguese)