About the Author

Mia Cai Cariello (she/her)

Mia Cai Cariello is an undergraduate fellow in the Global Arts and Humanities' 2020-21 Society of Fellows cohort. Cariello is a fourth-year women’s, gender and sexuality studies major with minors in human rights, Asian-American studies and studio art. She was the president of Take Back the Night at The Ohio State University since 2019-2021. Cariello will be continuing her research on anti-rape activism at Ohio State as a graduate student in the Department of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies.

Introduction

Anti-rape activism has been a consistent presence here at The Ohio State University since at least the 1970’s. The university has had its fair share of sexual violence instances, including the gang rape of a lesbian student on the Oval in the 1970’s; a gang rape committed by athletes (in an event referred to as Steebgate) in the 1980s; continuous abuse by former Ohio State physician Dr. Strauss through the 1980’s and 90’s; and most recently, an incident of two Ohio State football players being charged with allegedly raping and kidnapping a female student in 2020.

While anti-rape activism has been the source for several great improvements to campus — such as the lights and emergency call boxes on the Oval and partnership with SARNCO’s trauma-informed advocates — there is still a lot of work to do. Through analyzing and contextualizing the experiences of two alumna, Ella Lewie and Molly Pierano, with the data collected for the Reclaiming Our Histories Project, I have identified key themes and obstacles to anti-rape activism at Ohio State and anti-rape activism beyond the university setting.

“Our society is lacking in sex education but also in helping people understand how to discuss and create healthy boundaries and relationships.”

Ella Lewie

Interviewees

Molly Pierano

Molly Pierano was a student at The Ohio State University from 2008-12 and later returned as a staff member. Pierano is now the interim Title IX coordinator and director of education and engagement in the Office of Institutional Equity. They have worked closely with Ohio State's Title IX Office since 2016.

Ella Lewie

Ella Lewie is an alumna of The Ohio State University. While working toward her bachelors and master's degrees in social work, Lewie established Ohio State's It’s On Us chapter in 2018. Lewie went on to be a Policy Fellow with the ACLU of Ohio.

“I don't know that sexual violence itself has changed...but I think our response to it has.”

Molly Pierano

I have conducted one-on-one interviews over Zoom with two alumnas — Ella Lewie and Molly Pierano. I then transcribed these interviews with the assistance of Zoom’s software. I reached out to these two specific alumnas because their experiences have overlapped and intertwined for nearly a decade, and they offer the unique perspective of a student activist compared to a student-turned-staff member. I utilized interview methodology and narrative discourse analysis to examine what these two interviews can tell us about Ohio State rape advocacy.

Sexual Violence is not held within the vacuum of university life. Factors outside of Ohio State play a large part in what the university has to address in their programming and priorities.

- Ohio State is inherently constrained as a public university

Universities such as Ohio State that are funded by federal funds, donors and sponsors must account for many different stakeholders. These stakeholders' immediate prerogatives may not be in complete alignment with student and survivor activists’ needs. When anti-rape crisis centers were run primarily by grass-roots organizations such as Women Against Rape in the 1970s-1990’s, the stakeholders shared more equitable power with one another because it was largely a community volunteer organization. However, the downside to grassroots organizing for issues as traumatic as anti-rape activism is that that there was a constant need for more volunteers and funds due to burnout and demand for services. When rape crisis centers and other survivor support services became more institutionalized, they gained access to more stable funding and staffing, but this came at the price of autonomy over political activism and resource allocation.

- Shame and the stigma of sex

While neither explicitly states as one of the barriers to their work, both Lewie and Pierano’s interviews speak on the power of shame that surrounds not only survivors speaking up but also sex in general. Lewie mentions how she “really didn’t have a lot of experience talking about sex, and most of us also came from abstinence-only education.” Pierano stated that if she had knowledge of the resources available now, she believes “there would have been less self-blame, victim-blaming but, again, we [Pierano & undergraduate peers] weren’t really having those discussions.” While these topics remain somewhat taboo, both observed that they have noticed students in the later 2010’s being more open to discussing them, especially after specific cultural instances such as the “Dear Colleague Letter” and the #MeToo Movement.

Outcomes

- Lewie and Pierano both qualify their narratives as only being a part of the Ohio State experience, frequently stating that even though they had a particular experience that it does not mean it was universal around Ohio State's campus.

- Lewie and Pierano both make a point to acknowledge that they are cis white women, and that they must intentionally seek out other perspectives to ensure their advocacy work is as intersectional and accessible as possible.

- Pierano does not identify as doing “activism;” instead she emphasizes her advocacy — I believe this is due to her positionality as a current staff member. Lewie, however, does identify with doing activism.*

*Distinguishing activism and advocacy: Lewie and Pierano do similar work advocating for and with survivors; however, I am distinguishing their work with these two words because this is how they have self-labeled their own work.

Obstacles identified by Pierano

The following obstacles were identified by Pierano as interfering with or inhibiting her anti-rape advocacy:

- Students do not typically know what rights they have under Title IX.

- Staff worked to capacity cannot dedicate the time to create additional educational programming around other protected classes.

- Federal guidelines can drastically change policy and procedures at Ohio State without much input from those working in the university's Title IX Office.

Obstacles identified by Lewie

The following obstacles were identified by Lewie as interfering with or inhibiting her student anti-rape activism:

- Registering It's On Us as an active student organization.

- General lack of awareness by the student body of support resources on campus.

- Support resources on campus lack of capacity to meet the needs of all Ohio State's students, staff and faculty.

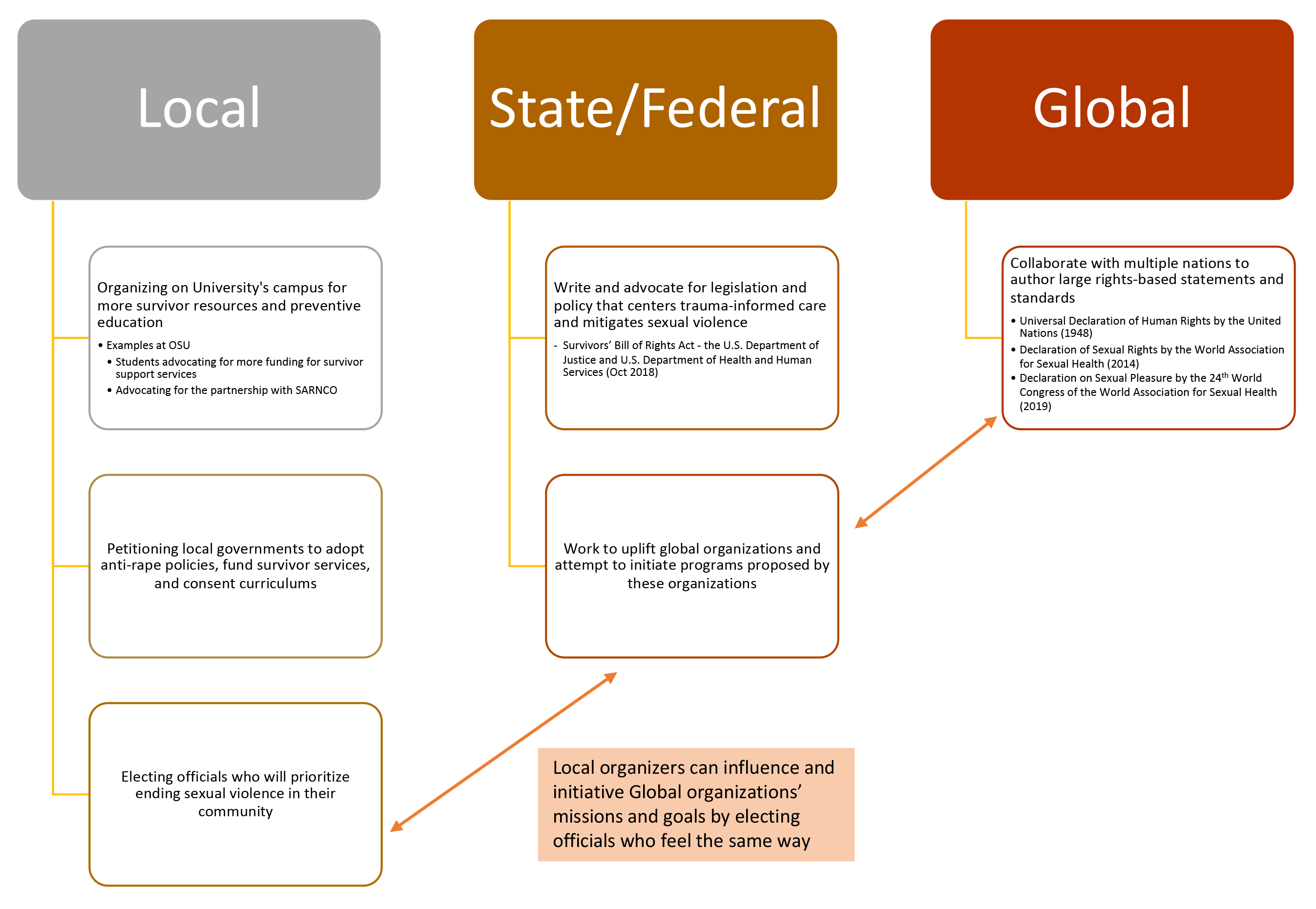

- Stresses how more individuals need to get involved with local, state and federal politics to push for more survivor- and consent-friendly legislation.

Pierano and Lewie’s work have both aided in the culmination of the following results:

- Registration holds for incoming students if they do not complete student sexual misconduct prevention education online course: “U Got This!”

- On-campus partnership with the Sexual Assault Network of Central Ohio (SARNCO) as a confidential resource.

From these interviews, I have come to the conclusion that anti-rape advocacy and activism through a student-activist lens and through a staff lens, while somewhat differently constrained, result in fundamentally the same desires:

- Center the people most impacted by sexual violence in the discussion and drafting of policies.

- Advocate for more funding to support resources for those imapcted by sexual violence.

- Funding for preventative education.

Evaluating what I have gathered from these interviews and accompanying articles, there have been changes to Ohio State culture around sexual assault awareness and prevention. Moreover, changes by students or staff within Ohio State can make campus a more supportive space for survivors of sexual violence. Yet, Ohio State cannot combat this issue alone. No additional changes or reforms within the university can really eliminate the root of the problem, which starts much younger than university-age students. Calls to action, such as Lewie’s to get more people involved with politics, are a through-way to possibly utilizing a human rights framework to uplift survivors of sexual violence and to inform future policies. However, it must be noted that utilizing a human rights framework in this way remains reliant on State power and institutions. While neither Pierano or Lewie suggested working beyond these limitations, one must critically consider if these systems of government can actually work and can enact changes even when itself is a perpetrator of violence.

- Color of Violence: The INCITE! Anthology

- Reclaiming Our Histories: Anti-Rape Organizations and Protests at The Ohio State University, 1970s to Present

- The Ohio State University Office of Institutional Equity

- Sexual Assault Response Network of Central Ohio