About the Author

Jaret Waters (he/him)

Jaret Waters is an undergraduate fellow in the Global Arts and Humanities' 2020-21 Society of Fellows cohort. Waters is pursuing dual majors in Spanish and economics and minors in geography and Portuguese. He researches the sociopolitical and cultural dynamics of Latin America, with a particular interest in migration, race and the environment in Brazil, Venezuela and Colombia. Waters is concurrently completing a project related to the geographies of Venezuelan migration in Brazil. Following his graduation in spring 2021, Waters would like to work in the immigration field in the United States, with the objective of better understanding border practices at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Project Overview

The well-renowned Brazilian activist Preta Rara has garnered international attention for affirming that “a senzala moderna é o quartinho de empregada” (translation: the modern-day slave quarters are the maid’s quarters), due to the racist, classist and gendered history of domestic work in the country. Through my research, I aimed to determine what other spaces are used to confine maids, nannies and other domestic workers to a subordinate position in modern-day Brazil.

Abstract

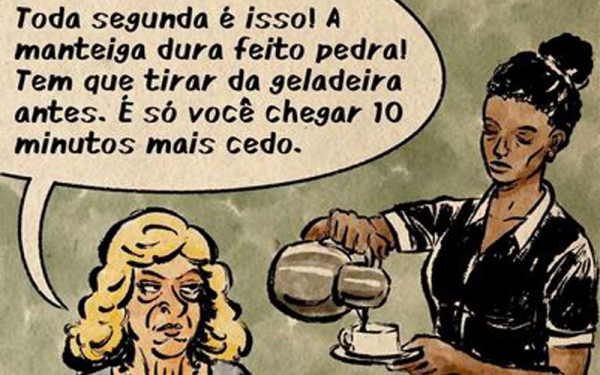

In Brazil today, it is estimated that over six million people are domestic workers, exercising tasks including maintenance, cleaning, childcare and cooking in the homes of their employers. Due to the country’s history of colonization and slavery, the majority of these workers are Black women. As such, for centuries now, Brazil has produced stereotypical images of domestic workers, quite similar to the images of Aunt Jemima seen in the United States. In addition to the discursive mockery of these workers, in practice, they often face exploitation, abuse and wage theft in their jobs.

This project, in particular, was inspired by the Black Brazilian activist Joyce Fernandes — more commonly known as Preta Rara — a third-generation domestic worker who inevitably left the profession and has since become a voice for the industry. In her TedTalk, she affirms that the modern-day slave quarters are the maid’s quarters. It was this statement that led me to question other spaces that exist that continue to subject domestic workers to the classist, racist and gendered oppression born out of the colonial period.

In order to respond to this question, I analyzed a series of Brazilian case studies from the past seven years. These case studies included films, comic strips, testimonies from domestic workers and new headlines, all speaking in some way to the relationship between domestic workers and the spaces they occupy. I was able to analyze a wide variety of spatial constructions, including separate bathrooms, separate ‘service’ elevators, favelas (‘slums’) and, of course, the maid’s quarters. In doing so, I came to several conclusions:

- Firstly, I found that many spaces are used to displace and disconnect domestic workers from their social and familial networks in order to bring them into an authoritarian or paternalistic relationship with their bosses.

- Secondly, many spatial practices are used in order to mark these workers as foreign when occupying the same spaces as their upper-class, white employers.

- Thirdly, there is a paradoxical segregation and integration that happens in the home that aims to dehumanize the bodies of these women.

Overall, these findings confirm that there is an undeniably spatial nature to the conception and treatment of domestic workers in Brazil. Because the case studies I analyzed told these narratives from the domestic workers’ perspectives (rather than traditional, stereotypical perspectives), it became clear that these spaces are constructed. They are not natural. This indicates that they can be deconstructed. Looking forward, future research should consider the ways in which domestic workers use these same spaces as a form of resistance.

Dedication

I would like to dedicate this work to Eula Anderson, the woman who led me to seek answers to these questions.